Should we celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation’s 150th anniversary?

Posted September 22nd, 2012 by James DeWolf PerryCategory: Public History Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Battle of Antietam, Battle of Sharpsburg, Emancipation Proclamation

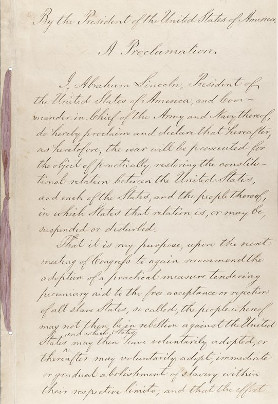

Exactly 150 years ago today, on September 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued his first Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that as of January 1, 1863:

Exactly 150 years ago today, on September 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued his first Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that as of January 1, 1863:

… all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.

Should we celebrate this declaration without reservation? Or should we, instead, see this as the anniversary of a tentative, morally ambiguous step, one which historian Richard Hofstadter declared to have “all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading“? ((Richard Hofstadter, The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948).))

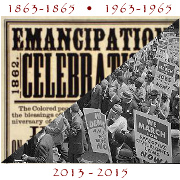

Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and the final Emancipation Proclamation issued on January 1, 1863, transformed the Civil War, declaring for the first time that the emancipation of all southern slaves was a Union war aim. As a result, some 4 million enslaved men and women were eventually liberated. Moreover, the Emancipation Proclamation has served as an inspirational milestone on the slow, tortuous path towards civil rights for black Americans and, indeed, for freedom and equality for all Americans.

What, then, is tentative or morally ambiguous about the Emancipation Proclamation?

The background

Until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, President Lincoln had always maintained publicly that the Civil War was not about ending slavery, but about preserving the Union.

Indeed, the Union public was generally not in favor of the emancipation of southern slaves, and it was widely understood that the Union army was not fighting for that outcome. As Sergeant William Pippey, of the 29th Massachusetts Regiment, wrote in the summer of 1862:

If anyone thinks that this army is fighting to free the Negro … they are terribly mistaken.

However, by 1862, Lincoln was increasingly interested in establishing emancipation as a stated war aim, if for no other reason than that it was becoming increasingly clear that the Union needed to undermine southern slavery in order to win the war. Emancipation would thus be a valuable military measure, aimed at weakening the Confederacy’s economy and, by allowing freed slaves to enlist in the army, transferring a valuable resource to the Union side.

Lincoln conceded this would be a radical departure from the reasons the Union entered the war, and for which its soldiers had been fighting and dying. As he commented to T. J. Barnett, an Interior Department official, once the proclamation took effect, “the character of the war will be changed. It will be one of subjugation and extermination” rather than of reconciliation.

Because of the radical character of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln presented the document to his cabinet in July 1862, but, following their advice, did not announce his intentions publicly. Instead, he waited patiently for a Union victory, in order to announce the goal of emancipation from a stronger position, to minimize public backlash and avoid the appearance of desperation.

Lincoln’s opportunity came following the Battle of Antietam (or, as it was known in the Confederacy, the Battle of Sharpsburg) on September 17. This battle is most famous as the single bloodiest day in American history, and in military terms, was a tactical draw. But it was possible to see this stalemate as a Union victory, and five days later, on September 22, Lincoln took advantage of the situation to announce the Emancipation Proclamation.

What the Emancipation Proclamation actually said

The best-known limitation of the Emancipation Proclamation is that it exempted the border states, those slave states which remained on the Union side, from emancipating their slaves. This measure was necessary in order to ensure that Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky would remain on the Union side, after the border states had refused Lincoln’s pleas to adopt gradual emancipation.

The Emancipation Proclamation also declared that in portions of Confederate states then under Union control— eastern Tennessee, Missouri, parts of northern Virginia—slave masters need only declare their loyalty to the Union to keep their slaves.

Lincoln had carefully crafted the Emancipation Proclamation in other ways, too, to minimize opposition to it. Fugitive slaves were to be returned to masters taking an oath that they had not participated in the rebellion. States voluntarily emancipating their slaves would be offered “pecuniary aid” in compensation. And all individuals who remained loyal to the Union were to be offered compensation for the loss of their slaves.

In contrast, the Emancipation Proclamation said nothing about any compensation to be offered to freed slaves. In fact, on the subject of freed slaves, the proclamation declared that Lincoln would seek to implement a colonization policy, despite fiery statements from free blacks that Americans of African descent had as much right to live in the United States as anyone else.

A morale crisis in the Union ranks

Despite the sharp limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation, the notion that the Union was now fighting on behalf of freedom for enslaved blacks drew strong reactions from Union soldiers and the Union public alike.

In fact, the Emancipation Proclamation triggered the most serious morale crisis of the war among Union troops. For months, the proclamation was the focus of talk in Union encampments, and much of the talk was of resistance and desertion:

We “will not fight to free the niger. … There is a Regement her that say they will never fite untill the proclamation is with drawn … nine in Comp. G tride to desert”

— Private Simeon Royse, 66th Indiana (Army of the Tennessee), to his father

The backlash among the Union public

Public opinion in the northern and western states had never favored the emancipation of the South’s slaves. Radical abolitionism had always been a fringe movement, and while it had gained converts in the years leading up to the war, it was still a minority political opinion in September of 1862.

Thus the Illinois State Legislature would defy its president and pass the following resolution:

Resolved, that the emancipation proclamation of the president of the United States is … a gigantic usurpation, at once converting the war … into a crusade for the sudden, unconditional and violent liberation of 3,000,000 negro slaves.

While opinion among Republicans in the Union was sharply divided on the question of emancipation, Democratic Party views were much more unified. Thus Horatio Seymour, in his acceptance speech as the party’s nominee for governor of New York, proclaimed that Lincoln was “fanatical,” and explained his opposition to emancipation in part by saying that the “general arming of the slaves throughout the South is a proposal for the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine; of arson and murder unparalleled in the history of the world.” (Seymour won the governorship.)

The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, in fact, is generally credited with Democratic Party victories in the 1862 congressional election. As Henry Raymond, Republican national chairman and New York Times editor, told Lincoln, the surge in support for the Democrats, and their platform of peace negotiations with the restoration of slavery, was due to “the impression … that we can have peace with Union if we would” but that the president was “fighting not for Union but for the abolition of slavery.”

While Lincoln was able to weather the storm of public opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation, he would find that even in the final months of the war, he was barely able to convince a majority of the people’s representatives in Congress to support emancipation: The Thirteenth Amendment, which would finally declare slavery abolished throughout the United States, passed the U.S. House of Representatives by only two votes, and then only after failing to win passage and after intervention by Lincoln himself.

Conclusion

On the occasion of the centennial of the Civil War, the poet and historian Robert Penn Warren wrote that the North’s memory of the war had transformed into a mythical “Treasury of Virtue,” in which any northern sins of slavery or race had been washed away by the sacrifices of a mighty moral crusade to eradicate southern slavery. ((Robert Penn Warren, The Legacy of the Civil War (1961).))

The Emancipation Proclamation is a perfect example of the historical amnesia, the mythology, that gives rise to Warren’s Treasury of Virtue. Far from being a principled declaration by the Union of its intention to fight for the freedom of enslaved black Americans in the South, it was a tentative, expedient military measure, widely opposed in the North, offered by Lincoln only with the greatest caution, and embraced by public opinion only years later.

September 22nd, 2012 at 8:13 am

This was EXCELLENT!

September 23rd, 2012 at 9:28 am

Thank you. You succinctly summarize this moment in history. Your points align thoroughly with what I have come to understand about the introduction by Lincoln of this proclamation. Well done.

July 1st, 2013 at 3:24 pm

[…] was arguably more significant for the course of the war, and for its role in determining that emancipation would result at the end of the war. […]

July 2nd, 2013 at 11:39 am

[…] At the Tracing Center, we focus on the role of slavery and race in the causes, conduct, and consequences of the Civil War. The Battle of Gettysburg was certainly of strategic importance in determining the outcome of the war, namely, that the Confederacy would be re-incorporated back into the Union, and that emancipation would eventually become a reality throughout the nation. ((Even so, the Battle of Antietam was arguably more significant for the course of the war, and for its role in determining that emancipation would result at the end of the war.)) […]