Historical myths and coded slave quilts on the Underground Railroad

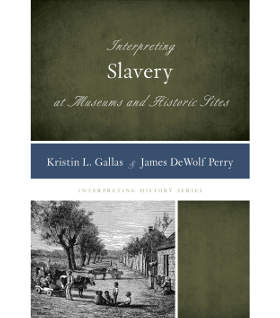

Posted March 29th, 2013 by James DeWolf PerryCategory: Public History Tags: American South, Northern emancipation, Northern slavery, Slave quilts, U.S. Civil War, Underground Railroad

Historian Paul Finkelman writes at The Root about the discovery of a sixth-grade reading comprehension test, online from the Massachusetts Department of Education, which reiterates the old myth that coded quilts were used to warn runaway slaves along the Underground Railroad.

Historian Paul Finkelman writes at The Root about the discovery of a sixth-grade reading comprehension test, online from the Massachusetts Department of Education, which reiterates the old myth that coded quilts were used to warn runaway slaves along the Underground Railroad.

This old legend, about coded messages in quilts which told escaped slaves of safe houses and routes to freedom, is common in the United States. Historians agree, however, that there is no truth to these detailed assertions; as Finkelman puts it, this myth has long been known to be “totally fabricated.” Nevertheless, the story of coded slave quilts has frequently been written about as truth, and the story often appears in the interpretation of slavery for the public at historic sites.

This is an appealing myth for many Americans, blending as it does the horrors of slavery with the bravery of the enslaved, who are seeking their own freedom; in some versions of the story, the quilts are even made and displayed by progressive white southerners, doing their part to fight the injustice of their society.

At the Tracing Center, we believe strongly in the importance of separating truth from fiction in conveying the history of slavery to the general public. Myths like that of the slave quilt never contribute to a better understanding of this history or its legacy today, and often exist precisely because they serve to obscure historical realities that would otherwise challenge comforting notions that keep us from deeper understanding of our heritage and its consequences.

For us, therefore, the most troubling aspect of the slave quilt story isn’t that black Americans didn’t help one another escape to freedom in exactly this way. It’s the frequent use of this story to put attention on white southerners who, supposedly, were instrumental in helping runaway slaves in this fantastical, rather heroic way. Instead, knowing that enslaved people in the South actually took tremendous risks with little support, and very little from white people, means learning more accurate and, ultimately, more fulfilling history.

The myth of emancipation in Massachusetts and the North

In this light, the slave-quilt story is hardly the only myth which props up a false narrative about the American experience with slavery. For instance, keeping our story in Massachusetts, there is also a pervasive myth, told in books, online, and at historic sites, that the state abolished slavery by law in 1783. This is said to have happened in a court case which supposedly turned on an interpretation of the state constitution. In fact, this case, Commonwealth v. Jennison, did not determine anything about the state constitution, or about the legality of slavery in Massachusetts. This is a myth which arose afterwards, and which supported the idea that the forward-thinking (white) citizens of the commonwealth had acted early, and decisively, to implement abolition.

Dismantling the myth that Massachusetts abolished slavery in the 1780s, and recognizing that this happened only generations later, has several consequences. Bringing this historical truth to light allows the public to grasp other historical information about the North’s role in slavery: to understand that slavery in Massachusetts and elsewhere died out only gradually, and largely for economic reasons; to realize that the end of slavery in the north was accompanied by widespread discrimination and the expulsion of free blacks from cities and towns; and to learn that the Civil War was, for most northerners, about preserving the Union and not, as many still believe, about fighting to end southern slavery, which was a goal only for a radical abolitionist fringe.

Just as importantly, demolishing the myth that the Massachusetts courts acted to emancipate the state’s enslaved population enables the public to better understand how emancipation was actually achieved in a northern state like this. Realizing that emancipation was not enacted by white juries or judges (or legislators) frees us to recognize that most of the hard work of fighting for freedom, even in a northern state, was done by free and enslaved blacks, working tirelessly and taking risks to win their freedom, and that of their loved ones, by escaping, or resisting, or fighting back, or buying freedom, or fighting court battles, as Quock Walker did in the legal action which led to Commonwealth v. Jennison.

May 12th, 2013 at 10:30 pm

Is there a museum or a tour of slave quilts history in North Carolina?

May 13th, 2013 at 8:07 am

The last I'd heard, there were quilts in the Historic Carson House in Marion, N.C., and the Cape Fear Museum, in Wilmington, as well as one in the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem and one in the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh. I would, however, strongly suggest calling any museum you want to visit, as none of these have extensive collections and my information may be out of date.

I would also advise caution, as there are still many museums and historic sites which offer information or exhibits on coded slave quilts, and as this blog post discusses, historians believe there never were any coded slave quilts.

April 11th, 2019 at 9:24 pm

Hello,

I author a blog on genealogical research with a focus on researching slaves and slavery in general. Can you recommend some scholarly sources (books, articles or authors) that dig a little deeper into this topic of the myth of underground railroad quilts? I have your first book and saw the documentary–both were excellent.

Robyn https://www.reclaimingkin.com

April 13th, 2019 at 1:22 pm

Thank you, Robyn. To my knowledge, no historian has seen fit to devote the time to a book or article debunking the myth of coded underground railroad quilts. (There's little reason an academic would do so, given that there isn't any sophisticated scholarly argument to be made; there is essentially no evidence for the existence of these quilts, which were first described in a children's book.) However, it's apparent that the vast majority who have expressed an opinion dismiss the notion out of hand, and several leading historians have taken the time to point out why in articles for the general public:

Renowned Yale historian David Blight, for instance, has publicly objected to this myth: https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2007/02/01/prof-de….

And historian Giles R. Wright debunked this myth in public repeatedly before his death, most notably here: http://historiccamdencounty.com/ccnews11_doc_01a…..