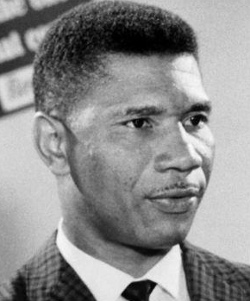

The assassination of Medgar Evers, 50 years later

Posted June 12th, 2013 by James DeWolf PerryCategory: Public History Tags: Civil rights movement, Medgar Evers, Myrlie Evers-Williams, NAACP

Yesterday, I wrote here on the 50th anniversary of one of the most momentous days in the history of the civil rights movement.

Yesterday, I wrote here on the 50th anniversary of one of the most momentous days in the history of the civil rights movement.

June 11, 1963 was a day of obvious, encouraging progress for the civil rights movement. It was the day when George Wallace was forced to step aside and watch the integration of the University of Alabama by Vivian Malone, James Hood, and the Alabama National Guard. That evening, President John F. Kennedy, released from the obligation to address the crisis in Tuscaloosa, made the last-minute decision to speak to the nation from the Oval Office anyway, announcing in hastily-prepared remarks that the civil rights movement was a moral issue without which the nation could not fulfill its promise of freedom, and promising the hastening of desegregation and the introduction of what would become the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.

I ended by noting, briefly, that hours after the president finished addressing his radio and television audience, there would be a horrifying event in Jackson, Mississippi. That event, of course, was the assassination of Medgar Evers, the outspoken NAACP field secretary for Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron de la Beckwith, a white supremacist, in the early morning hours of June 12.

Evers was returning home from a late-night meeting with NAACP lawyers, and was no doubt buoyed by the dramatic shift in both the tone and substance of civil rights policy emanating from the Oval Office. (Martin Luther King, Jr. responded to Kennedy’s speech by exclaiming, “Can you believe that white man not only stepped up to the plate, he hit it over the fence!”)

The murder of Medgar Evers quickly overshadowed the events of the day before. Shock and outrage over the assassination of a black civil rights activist, one who favored enforcing the law, extending the right to vote, and peaceful boycotts, generated nationwide attention and widespread sympathy for the civil rights cause. Evers was well-aware of the dangers of his work, having participated in the effort to locate witnesses in the murder of Emmett Till in 1955, and, in the weeks before his death, having personally faced death threats, a Molotov cocktail, and an attempt to run him down in the weeks leading up to his death. The obvious courage and conviction of Evers in the face of these threats only added to the national public’s mounting awareness, after his death, of the enormous risks being taken by civil rights activists in the South.

Those sentiments, in turn, developed into widespread anger and growing disillusionment with the platitudes of the Jim Crow system after two all-white juries, despite overwhelming physical evidence, were unable to convict Beckwith. Only in 1994, after evidence of jury-tampering emerged, and with the efforts of Evers’ widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, was Beckwith retried and found guilty.

Several weeks ago, I had the honor of hearing from Myrlie Evers-Williams, who was widowed fifty years ago today, at a breakfast meeting in Asheville, North Carolina.

Several weeks ago, I had the honor of hearing from Myrlie Evers-Williams, who was widowed fifty years ago today, at a breakfast meeting in Asheville, North Carolina.

Ms. Evers-Williams spoke powerfully, as she has for many years, as the widow of Medgar Evers, but she focused resolutely on the future. As someone with every reason to struggle with anger, bitterness, and hatred, she called for looking forward, in a spirit of racial healing. She didn’t shy away from our racial challenges, though, blending calls for healing and addressing bias and inequity, asking at one point for “the strength to stand a little bit longer to help change the face of hatred, prejudice, and racism.”

In an era when the civil rights legacy of Medgar Evers is under increasing assault, it is heartening to remember that the lasting legacy of his life, and sacrifice, include not only the achievements of the civil rights era fifty years ago, but also the continuing progress towards the dream of racial healing and equity in which we are engaged today.

Leave a Reply