Congress finally votes to abolish slavery, 150 years ago today

Posted January 31st, 2015 by James DeWolf PerryCategory: History Tags: 13th Amendment, Abraham Lincoln, Emancipation, Emancipation Proclamation, Harriet Tubman, U.S. Congress

Today, January 31, 2015, marks the 150th anniversary of the narrow but momentous decision, by a bitterly divided U.S. Congress at the end of the Civil War, to abolish slavery throughout the United States.

Today, January 31, 2015, marks the 150th anniversary of the narrow but momentous decision, by a bitterly divided U.S. Congress at the end of the Civil War, to abolish slavery throughout the United States.

Why the Union began to take emancipation seriously

In January 1865, the Civil War was in its final days. Yet many in the Union were still opposed to emancipation.

The abolitionist cause, while it had grown in popularity in the years leading up to the war, had always been a relatively unpopular movement in the North. The northeastern states had known slavery for more than two centuries, and most had only recently, and reluctantly, adopted emancipation laws themselves. Meanwhile, the northern economy was intimately tied to southern slavery: northern industry, shipping, and finance were heavily dependent on the cotton trade for their success, while Midwestern farms profited handsomely from transporting foodstuffs to slave plantations in the deep South.

When Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation at the height of the war, he was dramatically staking a claim as commander-in-chief that emancipation should be one outcome of the war. Yet his proclamation was only a limited, wartime measure, and congressional action was needed to put emancipation into effect. But the Union-controlled Congress refused to act, and with good reason: much of the northern public opposed emancipation, while the Emancipation Proclamation had created a morale crisis among Union troops. Union soldiers had marched to war to preserve the Union, and few had been abolitionist, much less interested in sacrificing their lives to free black residents of the South. This was not surprising, as relatively few of their families back home were interested in abolition, either, and the Emancipation Proclamation had generated political backlash across the Union.

Four years of struggle and sacrifice against the Confederacy had done much to change this situation. Union soldiers led the way, gradually coming to see emancipation as a means of revenge against the South and as a moral justification for the suffering and loss they and their comrades had endured. In many cases, too, Union troops had seen firsthand the courage and determination of the enslaved to live free lives, and of black Union troops to risk everything in the cause of freedom. The northern public, too, had changed, having spent years hearing from journalists and soldiers about the realities of southern slavery and the courage and determination of those who would be free. The war, in other words, had provided ample opportunity for northern ignorance and prejudice about black Americans to give way to greater understanding and appreciation. Consider the story of Harriet Tubman, whose Combahee River raid electrified a northern public that had not considered it possible for a black woman or an all-black regiment to conduct a successful, complex military raid into enemy territory, nor for enslaved blacks to want to rise up and risk their lives to escape to freedom.

Four years of struggle and sacrifice against the Confederacy had done much to change this situation. Union soldiers led the way, gradually coming to see emancipation as a means of revenge against the South and as a moral justification for the suffering and loss they and their comrades had endured. In many cases, too, Union troops had seen firsthand the courage and determination of the enslaved to live free lives, and of black Union troops to risk everything in the cause of freedom. The northern public, too, had changed, having spent years hearing from journalists and soldiers about the realities of southern slavery and the courage and determination of those who would be free. The war, in other words, had provided ample opportunity for northern ignorance and prejudice about black Americans to give way to greater understanding and appreciation. Consider the story of Harriet Tubman, whose Combahee River raid electrified a northern public that had not considered it possible for a black woman or an all-black regiment to conduct a successful, complex military raid into enemy territory, nor for enslaved blacks to want to rise up and risk their lives to escape to freedom.

The struggle to win emancipation

Nevertheless, emancipation was still not a very popular cause in the North. On June 15, 1864, the northern public’s elected officials in the U.S. House of Representatives voted to reject the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, repudiating the notion, nearly two years after Lincoln’s first emancipation proclamation, that the South’s slaves should be free as a consequence of the war. ((The vote in the U.S. House of Representatives on June 15, 1864 was 93 in favor and 65 against, or 13 votes short of the two-thirds majority needed to send a proposed constitutional amendment to the states for ratification.))

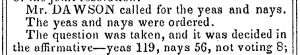

However, President Lincoln and his abolitionist allies (black and white) persisted, and found ways to win votes by offering incentives on other issues. On January 31, 1865, the House took up the amendment again, and this time narrowly passed the measure (by just two votes). ((The final vote in the House on the 13th Amendment was 119 to 56, barely reaching the threshold of a two-thirds majority.))

Abolition at last

The rest is history: President Lincoln signed the measure the very next day, and by year’s end, the necessary three-fourths of the states had ratified the amendment, bringing it into force and ending slavery by law throughout the United States.

The text of the Thirteenth Amendment reads as follows:

Section 1.

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The practical effect of this amendment was immense. The Emancipation Proclamation had created a patchwork of territories in which emancipation existed, at least in practice, under Union military control, and most northern states had ended slavery by law, at least by the end of the Civil War. But the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment extended emancipation by law, for the first time, through the nation, coast to coast, north to south, and did in practice ensure freedom for millions of Americans and their descendants.

There were certainly limits to the impact of this constitutional right: coerced labor, often of the very same people who had formerly been enslaved, and their descendants, would persist in many parts of the United States for generations to come. And there are those who link the amendment’s exception for criminal punishment, intended to allow the imprisonment of convicted criminals of all races to continue, to the issue of mass incarceration in our own time. Yet for the very first time, the United States could be said to be anti-slavery, and the long, slow quest to put this position into practice, and to obtain other civil rights for those who had endured slavery, and their descendants, could begin in earnest.

January 31st, 2015 at 12:25 pm

On behalf of the Slave Holding Me and all of her contemporaries, former Slaves, I know they sang ole songs sang in the cotton fields, secretly signaling a midnight escape to the “Underground Railroad” or as they labored and sang in church as they prayed for Freedom….”Thank You Lord, Amazing Grace..””Oh, Happy Day…”

I can almost feel and hear her chains being Removed……Ancestral Praise and Jah Love…thanks James ….Blessings be Upon your Family “Roots”, the DeWolf Slave Family, of Rhode Island, as Well,….Stella for the Slave